A CBBAnalytics explainer: Multiple CBBAnalytics tables are used throughout this piece. The highlighted number in the right column is the national percentile. For instance, the chart below is in reference to UAB’s Gaines/Ortiz/Johnson/Lendeborg/Davis lineup. That unit’s net rating is in the 70th percentile of all D1 lineups.

The UAB Blazers are seven games above .500 and sit fourth in the brutal American Athletic Conference. Their secret? Andy Kennedy has figured out his roster.

After months of discontinuity, the Blazers have at last fleshed out their starters and bench units; their massive influx of new players has finally synchronized. Today, we’ll look at the structure of UAB’s lineups and the substitution patterns that have contributed to the Blazers’ success.

The primary tools we’ll be using to evaluate these units are plus-minus, which reflects a lineup’s total point differential, and net rating, which measures a lineup’s point differential per 100 possessions.

The Blazers are nearly unrecognizable from who they were in non-con, so every statistic is for AAC games only unless noted otherwise.

I’ve categorized the Blazers’ units into three main groups:

“The shell” – lineups that feature the four-man backbone, or “shell,” that forms the core of UAB’s most successful units

“Secondary” – lineups that are the Blazers’ first options after Lendeborg or Davis is subbed out

“Other lineups” – this category includes Gainesless units and strange frontcourt pairings; they take up just 16% of UAB’s possessions

Let’s get started.

The Shell

Eric Gaines at point guard. Butta Johnson on the wing. Yaxel Lendeborg and Javian Davis in the paint. If this sounds like a winning plan to you, congratulations! You’ve discovered the groundbreaking strategy of “putting your best players on the floor.” Andy Kennedy, experienced coach that he is, has long adhered to this principle; UAB’s three most common lineups feature this four-man shell. They’ve been on the court together for a whopping 36% of the Blazers’ possessions in conference play.

Although structurally similar, the three lineups are differentiated by the guard that joins Gaines and Johnson in the backcourt. Each of UAB’s options provides a distinct benefit – Tony Toney slots in as a boost in energy and rim pressure, Daniel Ortiz spaces out the floor, and Alejandro Vasquez does a bit of both.

AJ has seen more recent playing time than Toney or Ortiz, and for good reason: magic happens when he’s on the floor with the core shell. The lineup of Gaines, Johnson, Vasquez, Yax, and Davis has a conference plus-minus of 24 points, in the 92nd percentile of all lineups nationally. Kennedy has recently been utilizing the fivesome as his closers; they were on the floor for the last nine minutes of regulation against North Texas.

They don’t do any one thing spectacularly, but they do everything well. By net rating, the core four + Vasquez has been UAB’s third-best defensive and second-best offensive group. Gaines, Butta, and AJ synchronize particularly well – when they’re on the floor together, the Blazers get to the rim at an obscenely high rate and make field goals at an incredible 51.4% clip. The lineup’s only major sin is committing too many fouls.

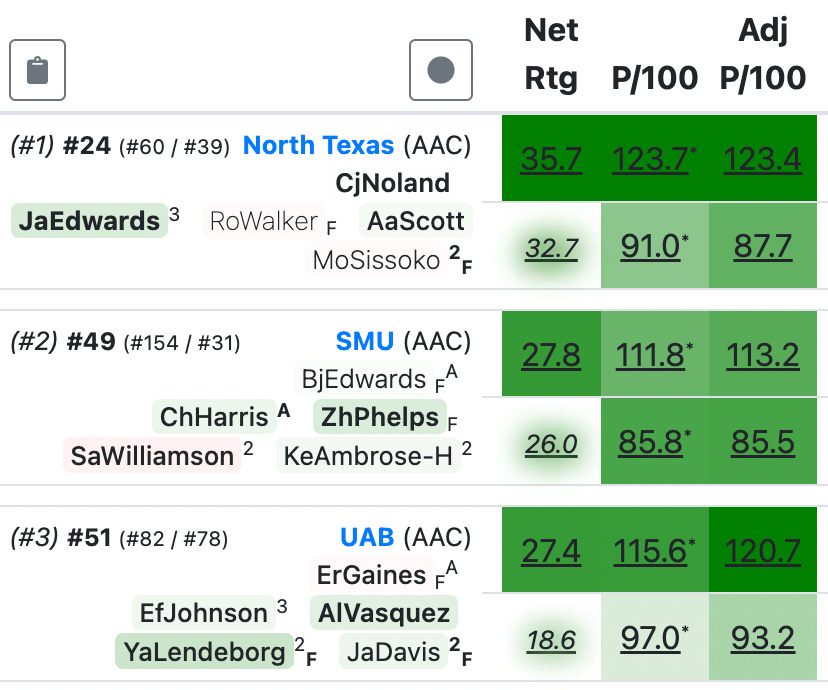

Per hoop-explorer’s adjusted points per 100 metric, this UAB lineup has been the third-best in all of AAC play, trailing only the North Texas and SMU starters.

Kennedy has taken note of this success. Gaines/AJ/Butta/Yax/JD has become UAB’s most utilized lineup by far – as noted in the chart above, they vacuum up nearly 20% of the Blazers’ possessions. Vasquez replaced Toney as a starter before the Tulane game and has moved into the primary small forward role.

AJ’s emergence has effectively made the Tony Toney variation of the shell lineup obsolete. The St. Bonaventure transfer has averaged 26 minutes a night since January 17th; Toney has averaged just 13. The Gaines/Johnson/Toney/Yax/JD fivesome, so prevalent in December and early January, has been on the floor for a total of three minutes in the last two weeks.

Kennedy has decided the Huntsville native is better suited to the secondary lineup, which we’ll discuss later.

Despite serving as UAB’s starting lineup for almost a month, the core four + Toney fivesome is one of the Blazers’ least effective weapons. As I mentioned earlier, the lineup excels at rim pressure; they have a free throw attempt rate of 78.0%, which ranks in the 97th percentile of all lineups nationally.

Unfortunately, the group isn’t good at much anything else. They have a plus/minus of -9 and a net rating of -15.6; both numbers rank in the bottom 25th percentile nationally. Their main problem is scoring – the Gaines/Butta/Toney/Yax/JD lineup sports an ugly 35.4% effective field goal percentage, and they’re one of UAB’s worst offensive rebounding units.

The dropoff between the Vasquez lineup and the Toney lineup is not as drastic as these numbers make it seem. Remember, we’re talking about conference games only – the sample size is small. Both units are likely due for some regression towards the mean.

However, it has become clear that Toney doesn’t mesh as well with the core shell and fits better into lineups featuring Daniel Ortiz and Christian Coleman. Toney and Javian Davis synchronize particularly poorly. Statistically, the duo has been an ineffective pairing on both ends; the Blazers’ net rating when they share the floor is -20.9. My best guess for why revolves around spacing – UAB already struggles to create room on the court, and combining the rim-centric Toney with the paint-bound center Davis exacerbates these problems.

I think there’s an amount of statistical noise here – for instance, opponents shoot 41.2% from three against JD and Toney, which speaks to some level of bad luck – but it’s clear that Kennedy would prefer Toney and Davis don’t share the court. Since the FAU loss, the duo’s shared minutes have dipped drastically, especially their shared minutes after halftime.

This lineup’s third and final variant sees Butta Johnson shift to the 3 and Daniel Ortiz slide in at the 2. This unit is the least common of the three we’ve discussed – it’s seen 38 possessions in conference play, while the Vasquez variation has seen 108 and the Toney variation has seen 58. The lineup saw its heyday in a January 2nd win over UTSA, but it’s been used spottily ever since.

The group has been successful in limited usage. It’s UAB’s best three-point shooting lineup, as one might expect with Ortiz and Butta roaming the wings. The fivesome makes a scintillating 60% of their triples, albeit on limited attempts. They don’t excel defensively – they allow a little too much dribble penetration and tend to commit too many fouls – but the unit certainly holds its own.

But the lineup gets away from the Blazers’ strengths, which I assume is the reason Kennedy hesitates to use it. The Gaines/Ortiz/Johnson/Yax/Davis group gets to the charity stripe less than any other UAB lineup: the unit attempts just 8.2 free throws per 40 minutes. That number ranks in the 11th percentile nationally.

The variant also doesn’t give UAB many driving threats; neither Johnson nor Ortiz are freight trains. However, the lineup is a valuable floor-stretching tool that shows opponents an unexpected look.

Secondary Lineups

The Blazers unfailingly start the game with one of the lineups mentioned above. They’ve followed this pattern since December; the last time UAB didn’t start the core four, they were blown out on the road at Arkansas State.

(The Blazers technically broke the streak against North Texas when Eric Gaines didn’t start, rumored to have been late to practice, but he was subbed on two minutes into the game. I’m not counting that.)

UAB’s first substitution is similarly predictable. In most cases, Kennedy will switch to a lineup with the following characteristics: Eric Gaines at the 1, a combination of various guards at the 2 and 3, Christian Coleman at the 4, and either Lendeborg or Davis at the 5.

These units have received a combined 31% of UAB’s possessions during conference play.

As you can see, the Blazers usually go to these Gaines/Coleman-led units the first time Lendeborg or Davis is subbed out. They typically proceed to close out the first half and appear sporadically after halftime.

Individually breaking down every single one of these lineups wouldn’t be particularly useful – there are eight different variations and many are nearly statistically identical. It’s more practical to discuss the general avenues of customization Kennedy has.

The first choice the coach must make: who mans the center position? With Coleman nailed to the 4 spot, there’s room for Lendeborg or Davis, but not both.

Lineups headed by Lendeborg have generally been stellar, while lineups headed by Davis…

Again, we’re talking about a sample size of eight games – the disparity between these two groups isn’t as significant as it seems. The Lendeborg units’ stats are inflated by a monstrous six-minute stretch against Memphis.

Still, it’s hard to argue that Yax shouldn’t be the primary 5 in this setup, and the coaching staff agrees. Barring foul trouble, Kennedy has favored Lendeborg-lead secondary lineups as of late.

The next question is how to handle the two open spots in the backcourt. Do you attack the rim full-throttle by putting Vasquez and Toney next to Gaines? Do you gamble on shooting with an Ortiz/Johnson combination?

The identity of the center plays a vital role in this equation. If Lendeborg is playing the five, you’re more likely to see Vasquez/Ortiz or Toney/Ortiz in the backcourt. Conversely, if Davis is up front, Vasquez/Johnson or Ortiz/Johnson are probably in the game. As noted before, Kennedy is averse to combining Toney and Davis; he also seems to prefer putting Butta and Davis together in this construction.

I want to note the version of this lineup that features Tony Toney at the 3, Daniel Ortiz at the 2, and Yax in the paint. Since Alejandro Vasquez replaced him as a starter, Toney has been consistently excelling in this highly effective bench unit; the group is one of UAB’s fastest-paced lineups and scored almost at will in the Memphis game.

Other Lineups

Corollary to these backup units are the Gaines rest lineups, which have the same spine as the groups above – various guards at the 2 and the 3, Coleman at the 4, and Lendeborg or Davis at the 5 – except Daniel Ortiz runs the point instead of EG.

It’s hard to draw any statistical conclusions about the effectiveness of these units – the sample size is far too small. They’re often put in after UAB’s second substitution, and usually stay on the court for about three minutes around the ten-minute mark of the first half, which is the only time Gaines is consistently off the floor.

An interesting fact I found while researching: Kennedy seldom plays Yax and Davis together outside the context of the shell. If both Gaines and Butta aren’t supporting the two big men, they rarely see the floor simultaneously. When they do, the results are underwhelming.

Again, it’s hard to draw meaningful conclusions from limited data, but these units have performed very poorly on offense and defense. It seems that the only time the duo effectively coexists is when they can take advantage of the dynamism that EG and Johnson provide.

I didn’t cover lineups that have seen less than 10 possessions in conference play – they’re used too minimally to be remarked on. Many of these bottom-tier units use four guards or feature some combination of Barry Dunning and Will Shaver.

Here’s a meaningless fun fact: the Ortiz/Toney/Johnson/Dunning/Shaver lineup has a net rating of +110.2!