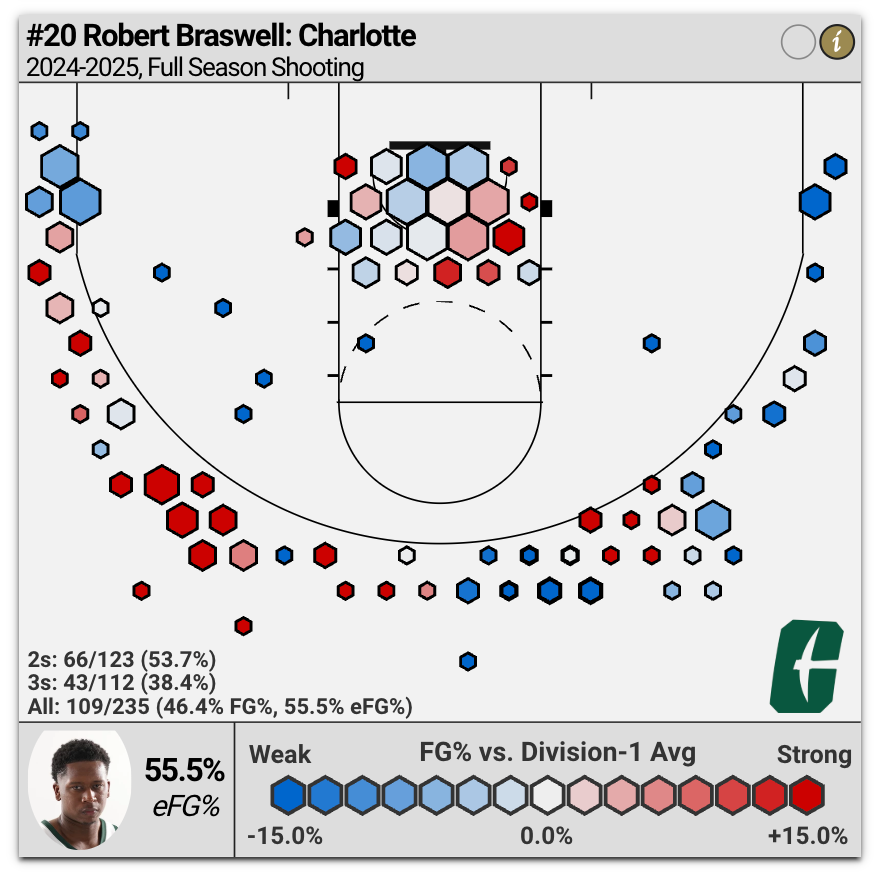

Charlotte 49ers (11-22, 3-15 AAC, 257th KP)

The UAB men’s basketball team first took the court in 1978-1979. Following a two-year acclimation period, Gene Bartow’s squad made its NCAA Tournament debut in 1981, during which it defeated 22-5 juggernaut Kentucky. One season later, the Blazers seized a #9 ranking in the AP Poll and broke into the national consciousness after reaching the Elite Eight.

The program’s rapid rise to prominence is a well-chronicled anomaly in the annals of the sport and is often described as unprecedented; UAB’s three-year turnaround between birth and success remains one of the most impressive achievements in the history of college athletics. But as Bartow set out to begin his inaugural season in Birmingham, there already existed a blueprint for quickly turning a young, metropolitan commuter school into a basketball powerhouse. As Opelika-Auburn News sports editor Perry Ballard wrote in 1978:

“In a sense, Bartow would like to turn UAB into another North Carolina-Charlotte, where that school’s basketball program has mushroomed so much that it has made NCAA appearances along with its big brother at Chapel Hill. UNC-Charlotte has prospered by fan support, and a tremendous reputation now.”

“When Bartow refers to that program, there’s a gleam in his eye.”

If anything, Ballard undersold Charlotte’s accomplishments. After making their Division I debut in 1970-1971, the 49ers finished as the NIT runner-up in 1976 before not only “[making an] NCAA appearance” in 1977 but rampaging all the way to the Final Four on the shoulders of future NBA Finals MVP Cedric Maxwell. It was apparent that Bartow saw the Charlotte model as one to emulate.

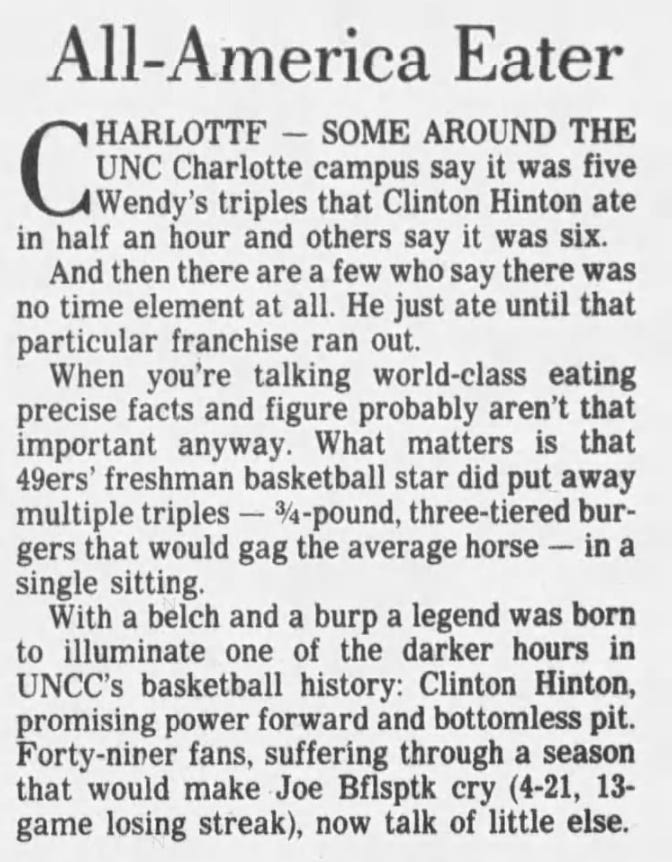

However, when Niners coach Lee Rose was poached by Purdue, it didn’t take long for that model to falter. As the 70s progressed, the Sun Belt — of which Charlotte was a founding member — began to pass the Niners by. Programs like UAB, VCU, and South Alabama rose to prominence, and the league’s 1982 additions of Western Kentucky and Old Dominion made the SBC landscape even more competitive. Less than ten years after achieving immortality, Charlotte became the conference’s punching bag, suffering through four consecutive seasons of single-digit wins in the middle of the decade. The most compelling story of the 1984-1985 campaign was forward Clinton Hinton’s Chestnut-esque rampage at a local Wendy’s.

Jeff Mullins, hired at the conclusion of the aforementioned season, eventually brought stability back to Charlotte. He never elevated the program to the heights of ‘77 but found consistent success over his decade on the sidelines, racking up three NCAA Tournament appearances and eight winning seasons. His successor, Melvin Watkins, won two March Madness games in two years before bolting for Texas A&M. Charlotte alumnus Bobby Lutz, an assistant on Mullins’ and Watkins’ staffs, was handed the reins in 1998.

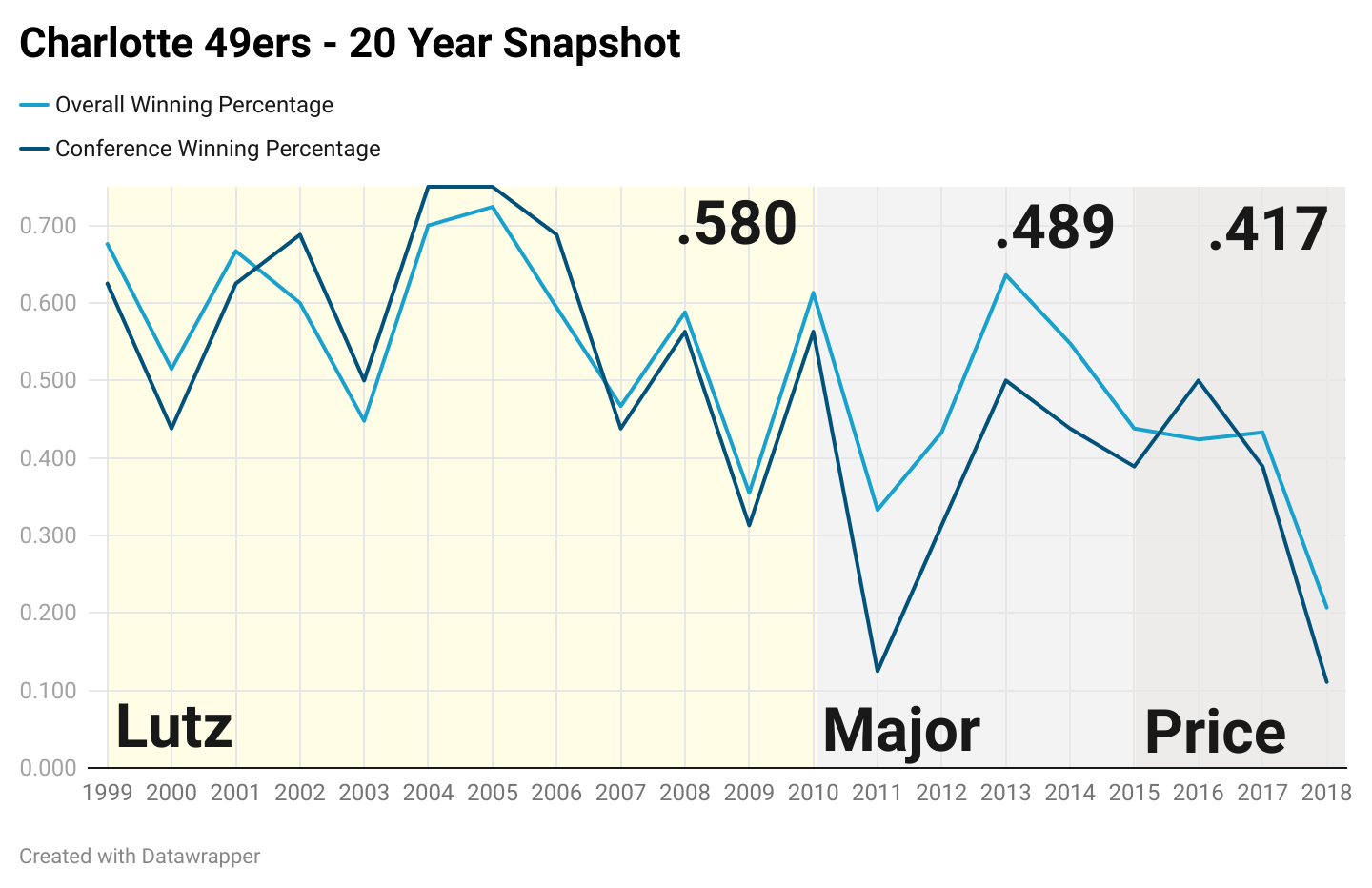

To make a long story short, Lutz‘s teams were phenomenal for the first seven seasons of his tenure, making five NCAA tournaments, but the Niners’ postseason pipeline dried up after 2005. Despite being the winningest coach in school history, Lutz was fired in 2010, days after his squad wrapped up a 19-12 campaign.

As is the case with many mid-majors that pass up consistency to swing for the fences, Charlotte has almost certainly regretted its decision. In letting go of Lutz, then-athletic director Judy Rose cited her desire to see the 49ers “compete in the NCAA tournament on a regular basis.” Instead of newfound success and glory, the program’s last decade-plus has been defined by failed attempts to recreate the Lutz days — failed attempts that have netted zero March Madness berths.

Ohio State assistant Alan Major, Lutz’s replacement, posted a 67-70 record over five seasons and departed in 2015 after having to take multiple extended health leaves. Former NBA star Mark Price lost an ugly 58.3% of his games and was fired a month into the 2017-2018 campaign. Houston Fancher finished out the year by going 3-17; needless to say, his interim tag was not removed.

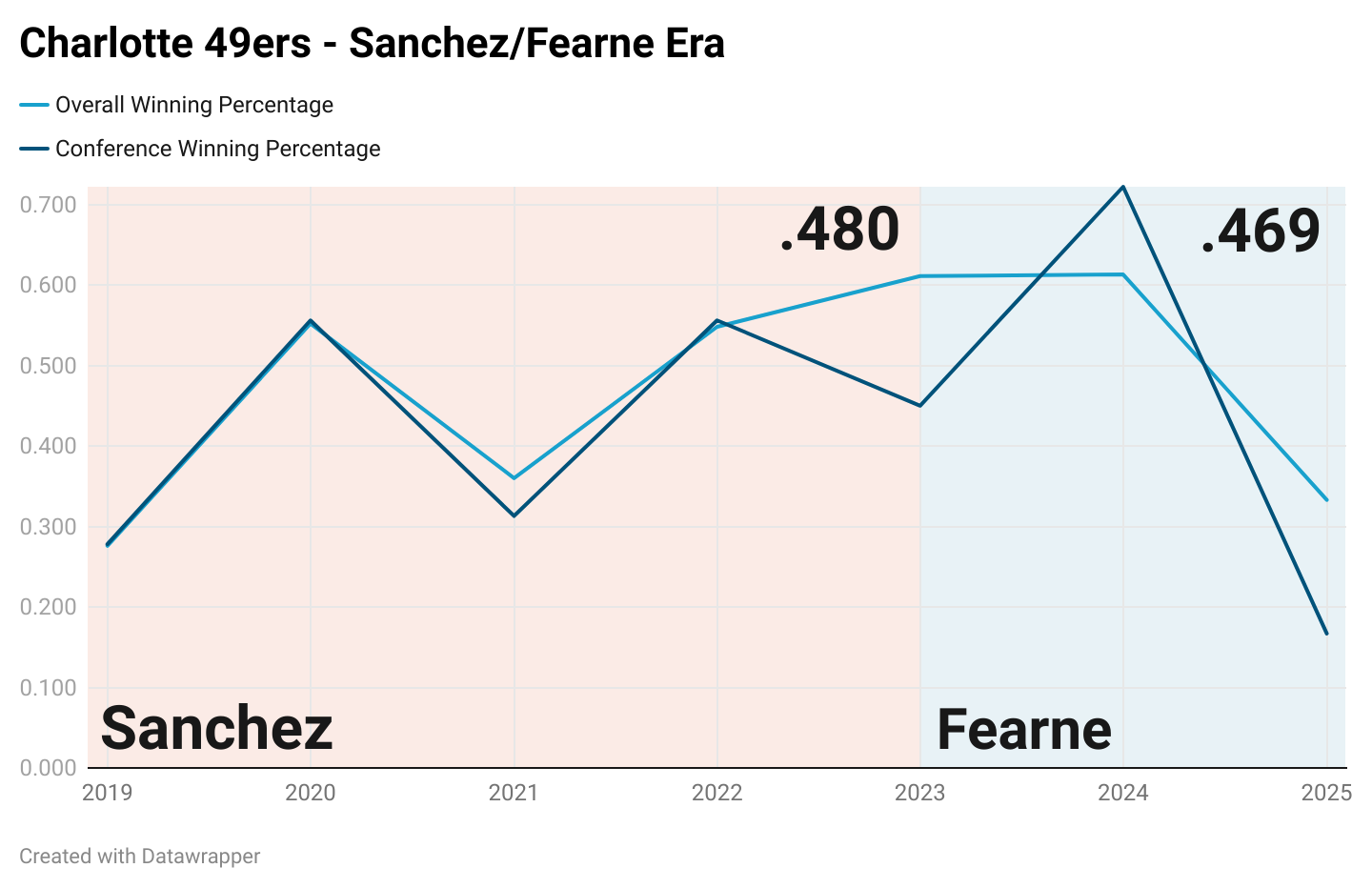

We’ve now arrived at our current destination: the Sanchez/Fearne era, which began in March 2018 with the hiring of the titular Ron Sanchez, a Virginia assistant. The Tony Bennett disciple ushered in a new chapter of the stylistic history of the 49ers, bringing the pack line defense to Halton Arena and grinding the team’s pace of play to a halt. The strategy served Charlotte reasonably well. Although Sanchez’s squad stumbled out of the gate, posting an 8-21 record in his first year, he proved to be perhaps the most consistent 49ers coach since Lutz, leading the program to back-to-back winning seasons in 2022 and 2023.

Sanchez’s magnum opus was the 2022-2023 campaign, during which the Niners claimed 22 victories — their highest total since Lutz was roaming the sidelines — and took home the College Basketball Invitational championship. Despite his team’s success, Sanchez gave up his position in June 2023 and returned to UVA as an assistant. He certainly elevated the program from the depths it sank to under Price, but like every other Charlotte coach since Lutz, Sanchez’s squads were consistently underwhelming in conference play and never sniffed March Madness — in fact, they failed to win a single C-USA tournament game.

Because of Sanchez’s oddly timed departure, Charlotte opted to eschew a national search, instead giving associate head coach Aaron Fearne the interim title. Shockingly, the following season saw the Niners rack up their most conference wins (13) since 1998, an achievement that earned Fearne the permanent job. The 49ers didn’t just stay afloat in the new-look American, they ran through it, at one point rattling off eight consecutive AAC victories.

I’ll speak from firsthand experience when I say that over the many years UAB has shared a conference with Charlotte, I cannot remember its fans talking about their basketball coach with anything but derision and pessimism. As the 49ers knocked off a ranked FAU, crushed North Texas, staged a massive comeback to beat UAB, and sold out Halton during a cathartic smashing of rival East Carolina, I was seeing tweets come across my feed that I couldn’t believe:

It felt as though Charlotte had finally paid off the karmic debts it accrued from firing Lutz.

The 49ers faltered down the stretch (fumbling the league title to an equally revitalized South Florida), went yet another year without a conference tournament win, and were burned by the transfer portal in the aftermath of their dream season. However, they were expected to remain competitive in 2024-2025, receiving a preseason KenPom ranking of 128.

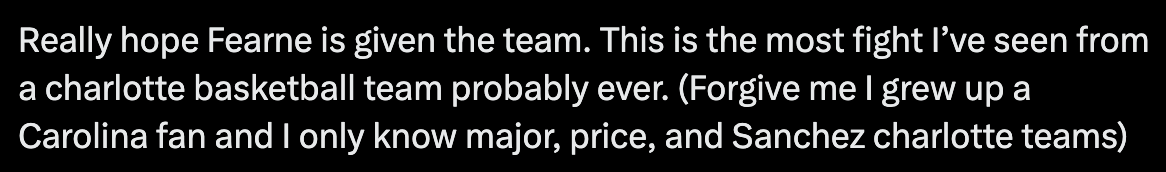

It wasn’t meant to be. What came next was nothing short of a disaster: Charlotte cratered to 11-22 (3-15), finishing last in the American by a full game. Any optimism left over from ‘23-’24 died quickly; by the third week of the season, it was apparent the magic had run out. A November 23rd loss to LIU — one of just two non-conference DI victories the Sharks accumulated all year — was followed by a November 27th smashing at the hands of East Tennessee State.

Although the 49ers proceeded to give Davidson a fight and beat Murray State in two overtimes, their analytical ranking just kept ticking down and down.

A December 22nd blowout at the hands of Big West bottom-feeder Hawaii set off a 2-11 stretch that dragged the 49ers to the depths of the conference leaderboard. It took Charlotte until January 22nd, when it knocked off South Florida, to get within five points of defeating an AAC opponent. No spark of hope ever presented itself to the 49er faithful; Fearne’s squad never strung together a stretch of play that constituted meaningful improvement. Once they dipped under 250th in Haslametrics’ rankings at the beginning of the new year, they remained under that threshold for 69 of the season’s remaining 72 days.

The Niners ultimately scrapped out tight decisions over Rice and Temple to finish 3-15 in American play, but they were a few bounces away from posting an 0-18 record. Charlotte’s consolation prize, so meaningless as to feel cruel, was a second win over Rice that — at long last — marked the program’s first conference tournament victory since 2016. The 49ers’ season mercifully ended when they were dispatched by FAU in the next round.

Seemingly on the verge of reclaiming its mantle as a proud program, a capable rival to its mid-major peers, Charlotte lost everything — players, momentum, the energy that prompted the above tweets. Fearne is now mortal, conceivably one bad campaign away from losing his job and going down in history as yet another failed successor to Lutz. A year removed from being on top of the world, the Niners are nearly back to where they started.

A dearth of ballhandling and playmaking talent

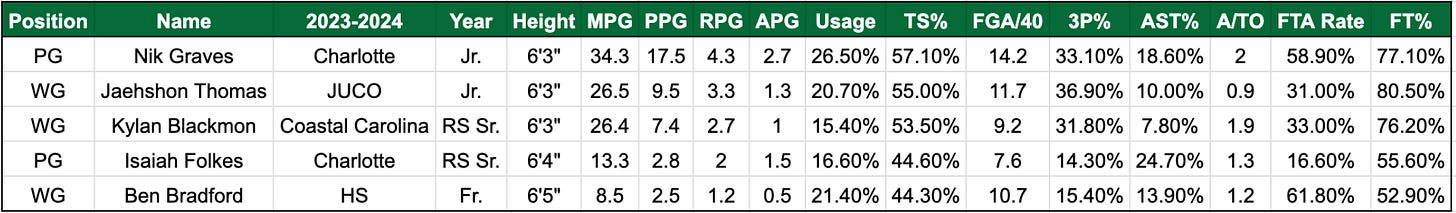

Why were the 49ers so bad? Let’s start with the offense, which ranked 217th in KenPom and third-worst in the conference. Charlotte’s 2024-2025 roster listed five players as guards: returners Nik Graves and Isaiah Folkes, transfers Jaehshon Thomas and Kylan Blackmon, and freshman Ben Bradford.

Out of that group, Graves and Folkes were the team’s ballhandlers, while Thomas and Blackmon were utilized more as wings. Bradford barely played in non-con and saw the court inconsistently throughout the AAC schedule.

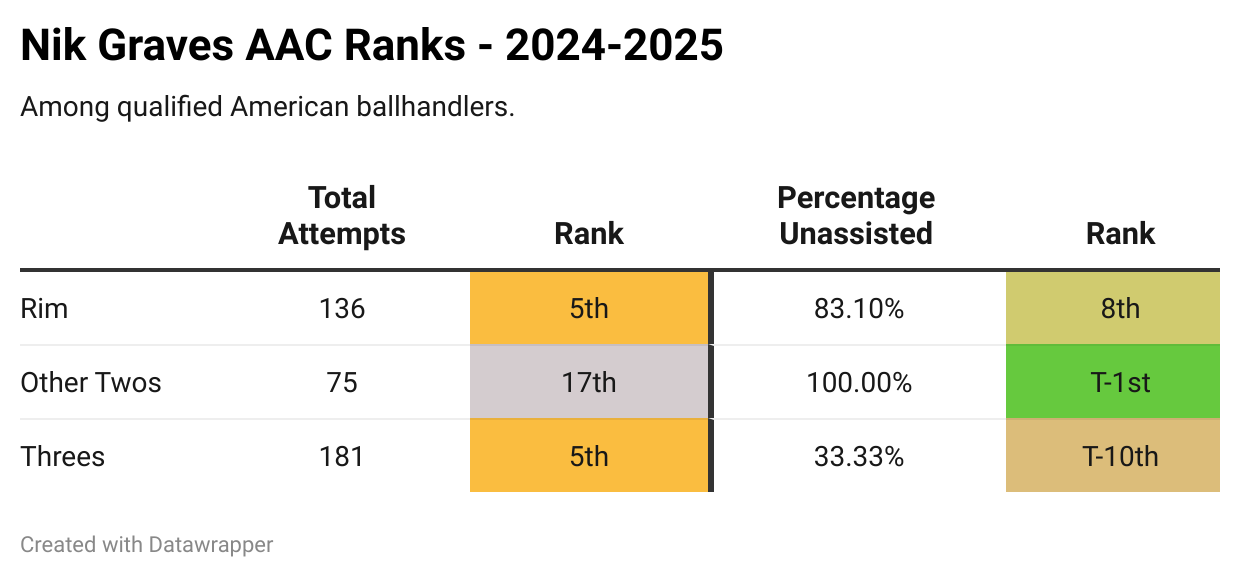

Graves, the Niners’ only consistent backcourt playmaker, performed admirably in taking over the reins from former Charlotte point guard Lu’Cye Patterson, perhaps even surpassing his predecessor. While not the most elite shotmaker or vertical athlete, Graves nevertheless averaged 17.5 points per game on higher efficiency than Patterson, creating his own shot at a rate unmatched by most of the conference’s ballhandlers.

Graves also drew fouls at an elite clip (among AAC players, he ranked only behind PJ Haggerty in FTAs per game) and posted a 2.0 AST:TO ratio while shouldering a 26.5% usage rate. Combined, these factors made him the AAC’s fifth-most valuable offensive player by hoop-explorer’s RAPM.

Folkes, on the other hand, graded out as a bottom-five offensive player in the conference. The longtime 49er, a well-known liability on the attacking end since his career began in 2020, was typically more of a shooting guard/wing in past seasons. In a ballhandling role, he posted a miserable 44.6% true shooting percentage and a mind-blowing 30.5% turnover rate.

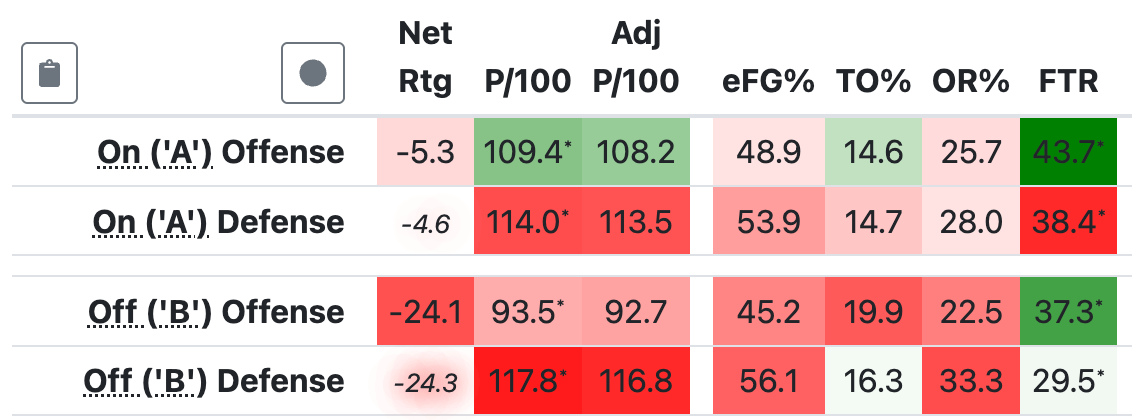

Needless to say, Graves was the lead guard Charlotte preferred. In the rare instances he left the court, the results were disastrous:

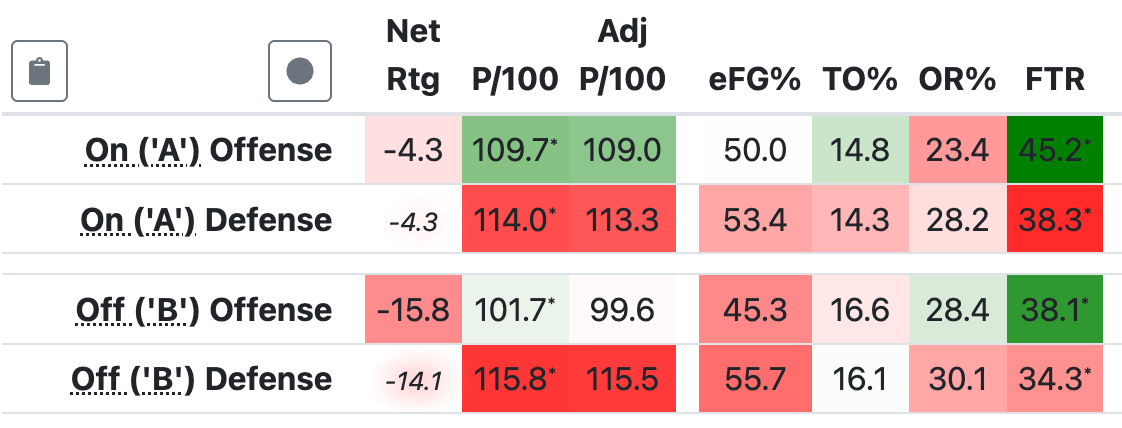

Per hoop-explorer, with Graves on the floor (lineup ‘A’), Charlotte’s offense performed like the 225th-best unit in the country. With Graves on the bench (lineup ‘B’), Charlotte’s offense dropped nearly 20 points in net rating and performed like the 355th-best unit in the country. There are 364 Division I teams.

If you feel like one effective ballhandler is a low number, you’d be right — many of the Niners’ offensive problems can be attributed to the fact that the vast majority of their shot creation and backcourt playmaking duties rested on the shoulders of a single player.

Underwhelming wing production

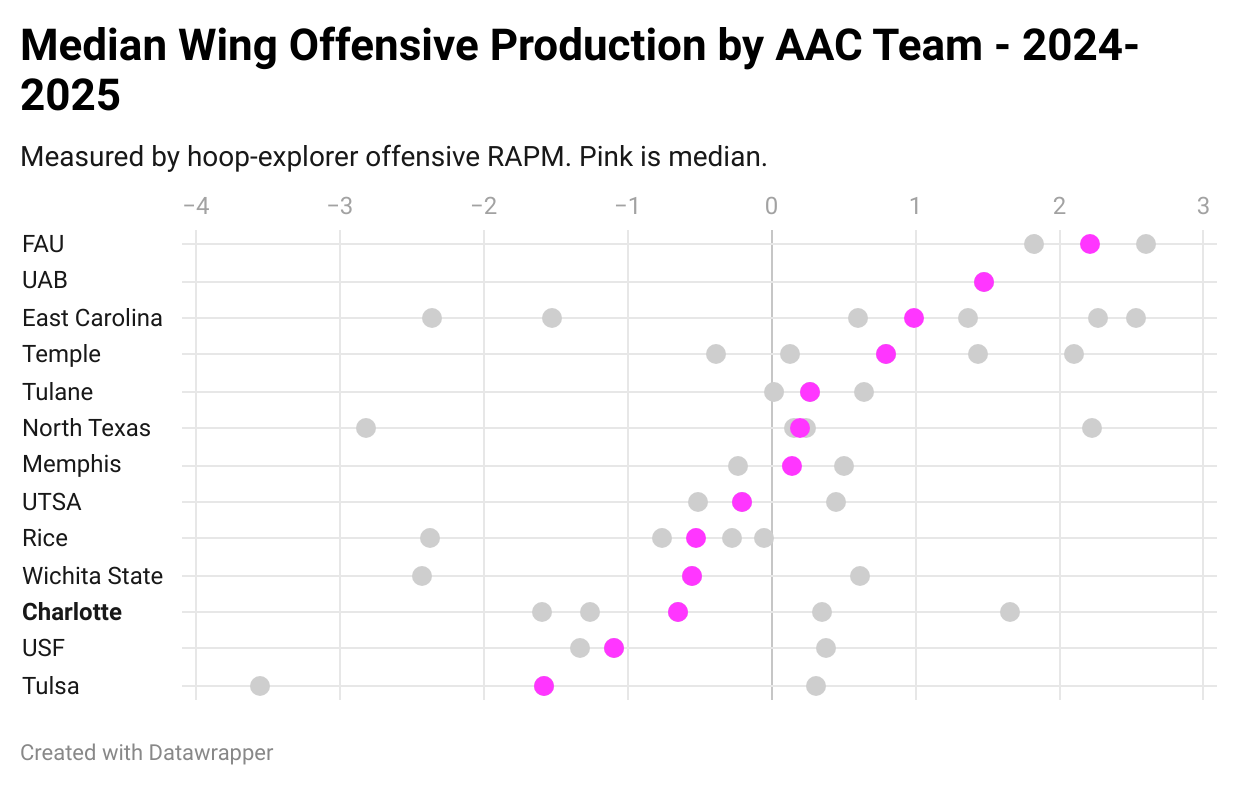

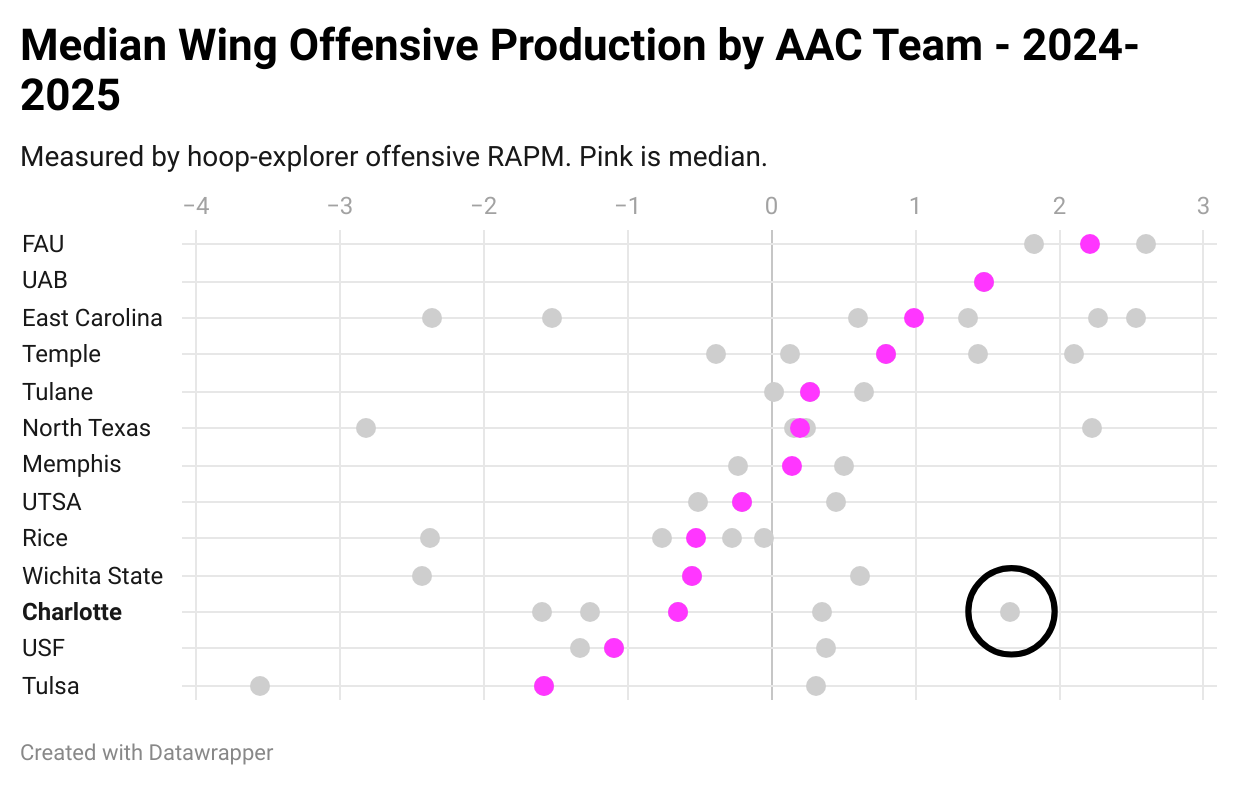

Graves was not aided by the fact that his team’s wings made up one of the least potent units in the conference. Below is a graph of the median offensive production every AAC squad got from their wings, measured by hoop-explorer’s offensive RAPM. Charlotte ranks below all of its peers except South Florida and Tulsa.

We’ll categorize Charlotte’s five wings into wing guards — Blackmon and Thomas — and wing forwards — Robert Braswell IV, Nika Metskhvarishvili, and Giancarlo Rosado.

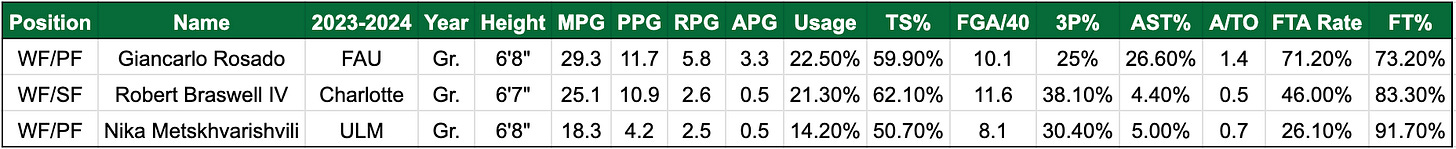

Starting with the former group, Blackmon was a 6’3” Coastal Carolina transfer who didn’t do much of anything but take triples and layups during his time at CCU. He performed in much the same manner in 2024-2025, rarely passing, creating his own shot at the lowest rate of any non-big on the team, and generally serving as a low-usage floor spacer on mediocre efficiency.

Blackmon almost never turned it over, was good for the occasional midrange bucket, and yanked down an average of one offensive rebound a game (a mark that tied him for the team lead), but most metrics pegged him as belonging to the bottom 25th percentile of AAC players on offense.

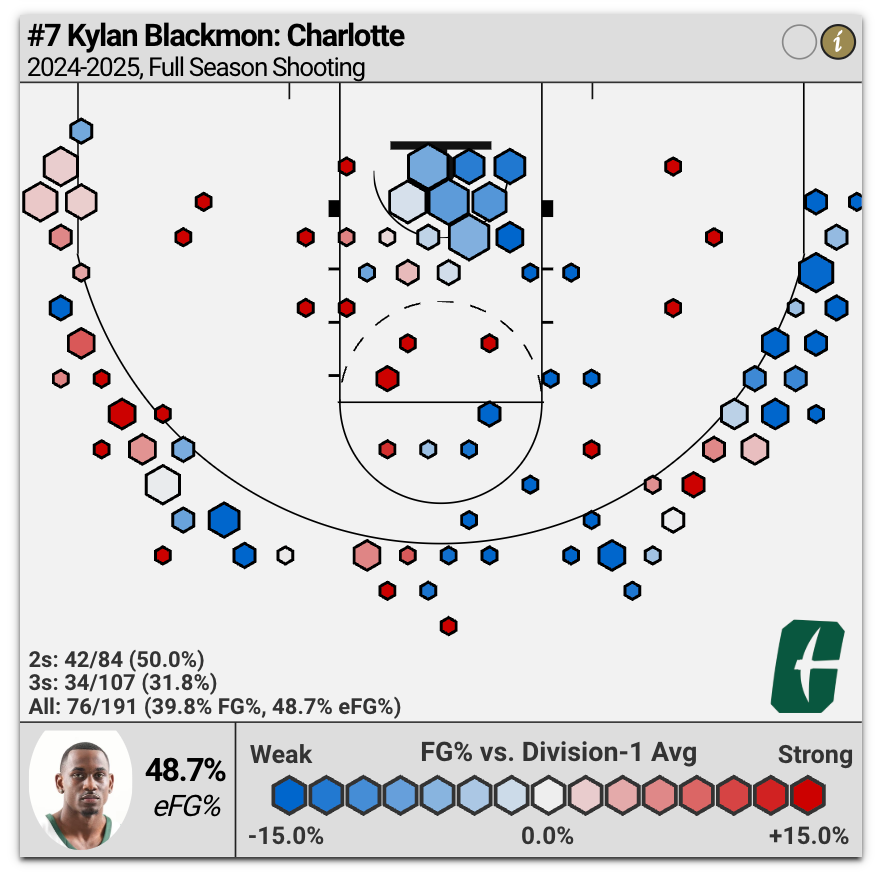

Thomas, a transfer from JUCO Florida Southwestern State, was more dynamic than his counterpart. He proved to be a more efficient rim finisher and maintained a better true shooting percentage despite assuming a slightly more complicated and higher-usage role. Thomas also knocked down 36.9% of his triples on roughly average volume.

However, he struggled to create his own shot, and although he was a more productive passer than Blackmon, those contributions were partially negated by his 25th percentile AST:TOV ratio. Despite being efficient when he got there, relatively few of Thomas’ field goal attempts actually came at the basket. Thomas’ shot chart paints the picture of a player who hadn’t yet learned to complete drives at the Division I level.

All in all, it was a transition season for Thomas, and it didn’t seem as though he was quite ready to be an effective offensive contributor in the AAC.

To reiterate a point made earlier, of the four ballhandlers and wing guards we’ve covered so far (the entirety of Charlotte’s backcourt stable), Graves alone was an efficient playmaker and shot creator. If you’ve also noticed a concerning lack of shooting talent in the backcourt, that’s an attentive observation, and I’ll go ahead and spoil it: Charlotte was the second-worst three-point shooting team in the conference. The Niners lived and died behind the playmaking/creation abilities of Graves and Rosado, whom we’ll arrive at momentarily.

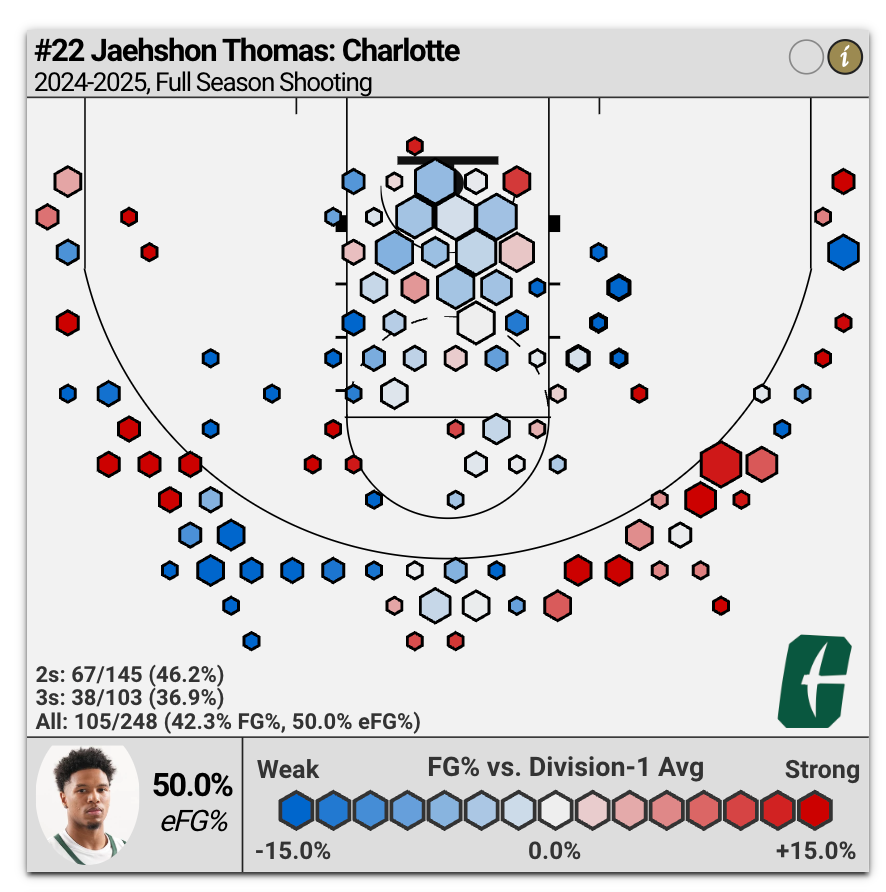

But first, the forwards Braswell and Metskhvarishvili. The former was an eighth-year (!!!) veteran whose final season was the healthiest and perhaps best of his career. The lone 49er (outside of the two aforementioned saviors) who posted a positive BPM in 2024-2025, Braswell didn’t take on a particularly complex role, as is made apparent by his shot chart:

As a rim-and-threes floor spacer, Braswell was a more efficient version of Blackmon. His primary offensive contributions were knocking down 38.4% of his triples, driving to the basket if the defense got overextended, and drawing fouls. He wasn’t a transcendent scorer by any means, but he was the most effective complementary attacking piece on the roster.

Metskhvarishvili’s case is sadder. During the dream 2023-2024 campaign, Charlotte ran a substantial portion of its offense through talented bigs Igor Milicic and Dishon Jackson and ranked among the nation’s top 40 most frequent employers of post-up driven action. It seemed as though Fearne’s idea was to pair Metskhvarishvili — a 6’8” ULM transfer with a knack for passing — with Rosado in order to replicate a version of the Milicic-Jackson battery.

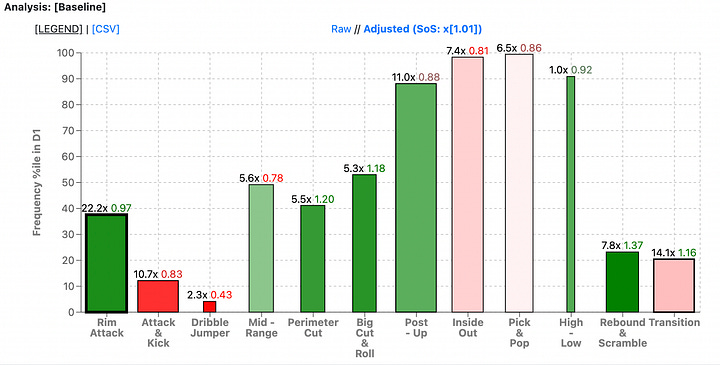

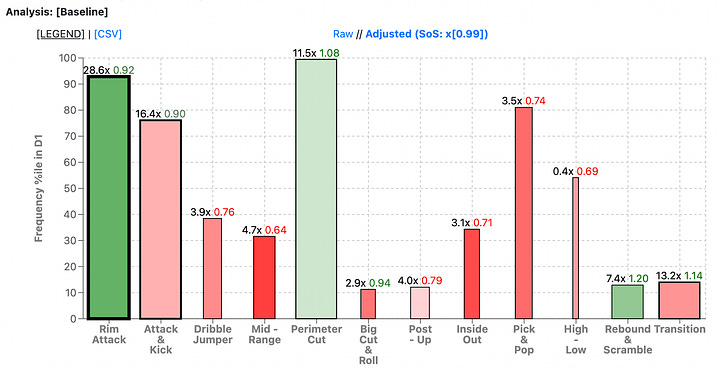

Instead, Metskhvarishvili missed several games with injuries and never really settled into his role — after averaging 12.3 PPG at ULM, only thrice did he break the ten-point threshold at Charlotte. This, in part, led to the Niners adopting a strategy much less centered around the post than it was in 2023-2024:

As a big body and a capable distributor from both the interior and exterior, Rosado acclimated well to the Niners’ driving and cutting-oriented attack. Going back to our wing RAPM chart from earlier, take one guess at who Charlotte’s outlier is:

That’s right — Vlad Goldin’s former backup at FAU spent the final season of his career with the Niners and took a developmental leap, serving as the roster’s only non-Graves player capable of passing the ball. Although his turnover rate was unimpressive, he made up for it by setting up a whopping 27% of his teammates’ field goals while he was on the court; Rosado actually led Charlotte in assists.

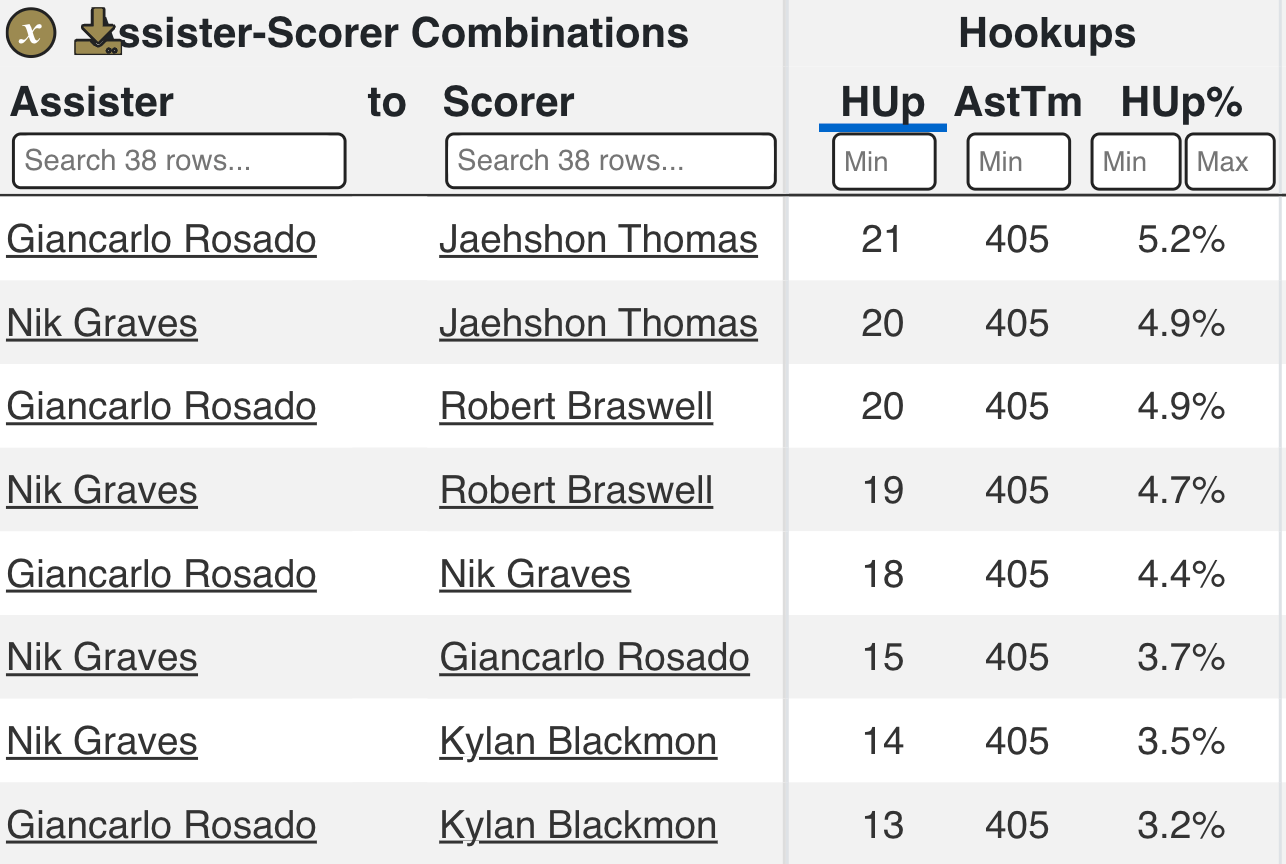

The Niners’ top eight assister-scorer combinations were Graves and Rosado finding a teammate, typically a cutter or a shooter, or Graves and Rosado finding one another:

Like everyone else on the roster sans Braswell, Rosado didn’t put up the most efficient numbers from the field, but he was by far the team’s best non-Graves shot creator and leveraged his 6’8” frame to shoot free throws at one of the 20 highest rates in the nation. Thanks in large part to the efforts of Graves and Rosado (and to the Niners’ overall lack of shooting talent), Charlotte ranked first in the nation in percentage of total points scored from the charity stripe.

Graves was the motor that drove the 49er offense, but Rosado helped keep it afloat by taking on a portion of the team’s playmaking and creation burdens. His on/off splits are slightly less dramatic than those of Graves, but they’re still significant: Charlotte’s net offensive rating dropped over 11 points in lineups not featuring him.

The conference’s least effective true bigs

I’m defining “true big” as a big that occupied more of a stretch four/center role rather than a wing/small forward role. The line between these groups is often blurred, but sorting players into neat categories isn’t the main goal in this case. Rather, it’s to emphasize that Charlotte’s stable of “true bigs,” according to this definition — the 6’7” Rich Rolf and the 6’10” trio of Dean Reiber, Nick Richart, and Aleks Szymczyk — was nearly unplayable.

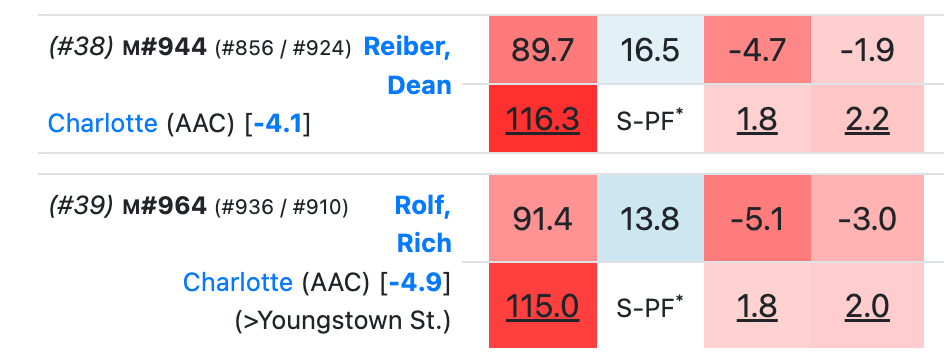

Szymczyk, a Florida transfer originally from Germany, saw fewer than 100 minutes the entire season and posted an effective field goal percentage of 37.0%, while Richart, a redshirt freshman, appeared in eight games and scored five total points against Division I competition. Reiber and Rolf enjoyed far more playing time, but according to hoop-explorer’s RAPM, they were the two worst overall frontcourt players in the entire conference. As AAC play progressed, both saw their minutes sharply decrease (Rolf in particular).

While still ineffective, Reiber’s passing skills made him a better offensive option than Rolf, who graded out at the bottom of the barrel.

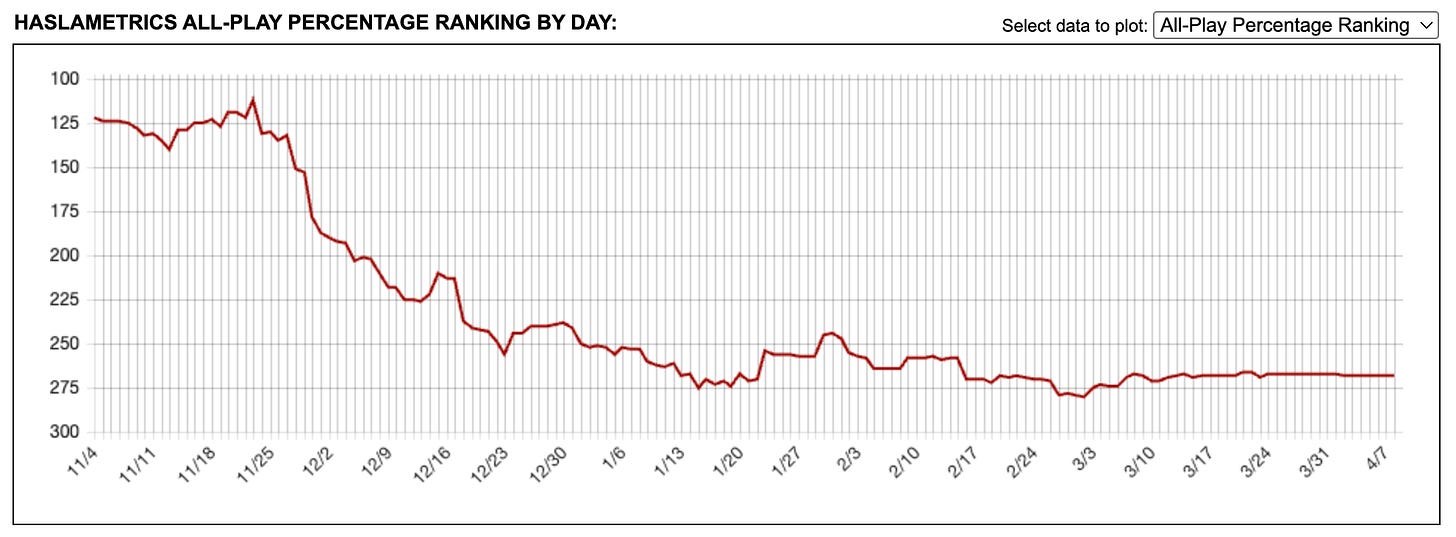

This lack of effective height tanked the team’s interior numbers and contributed to Charlotte’s overall shift away from post-oriented offense: the Niners finished 312th in offensive rebounding percentage, 291st in field goal percentage at the rim, and 306th in percentage of offensive shot attempts blocked. It also played a large role in an aspect of Charlotte’s struggles we haven’t discussed yet — its defense.

No defensive playmakers, low athleticism

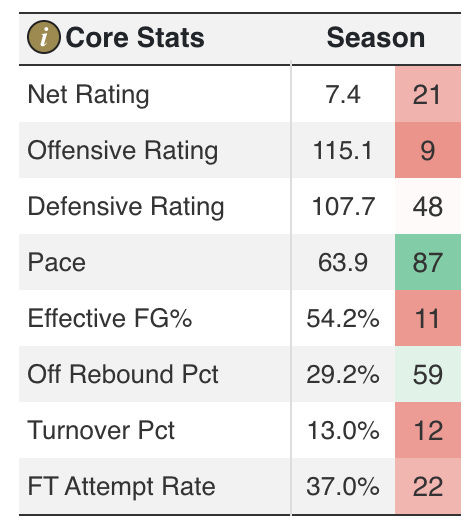

Charlotte’s defense ranked 288th in KenPom, lowest in the conference and the worst performance a 49ers team has turned in since the disastrous campaign that got Mark Price fired in December 2017. Fearne’s group allowed opponents to post a 54.2% effective field goal percentage and a whopping 56.4% two-point percentage, one of the highest marks in the country.

One of the Niners’ problems was that it was impossible to construct an backcourt grouping sound on both sides of the court. Folkes was the best defender on the team, but he was a huge liability on the attacking end. Graves demonstrated many strengths, but defense was not one of them; Blackmon graded out similarly poorly. Thomas, who saw the roster’s third-highest minute share behind Graves and Rosado, was the worst perimeter defender in the American and one of the 100 worst in the country.

Due to the aforementioned lack of effective height, Charlotte’s frontcourt didn’t fare much better, allowing over 67% of opposing rim FGAs to go in. Rosado posted the 13th-lowest block rate (0.7%) of any mid-major player standing 6’8” or taller; Metskhvarishvili didn’t make a significant defensive impact; Rolf and Reiber were invisible. Teams without a true rim protector can sometimes compensate if they have a bevy of athletic forwards/wings who can rotate back and contest shots, but only Braswell proved capable of consistently doing so, and his defensive metrics were ugly nevertheless.

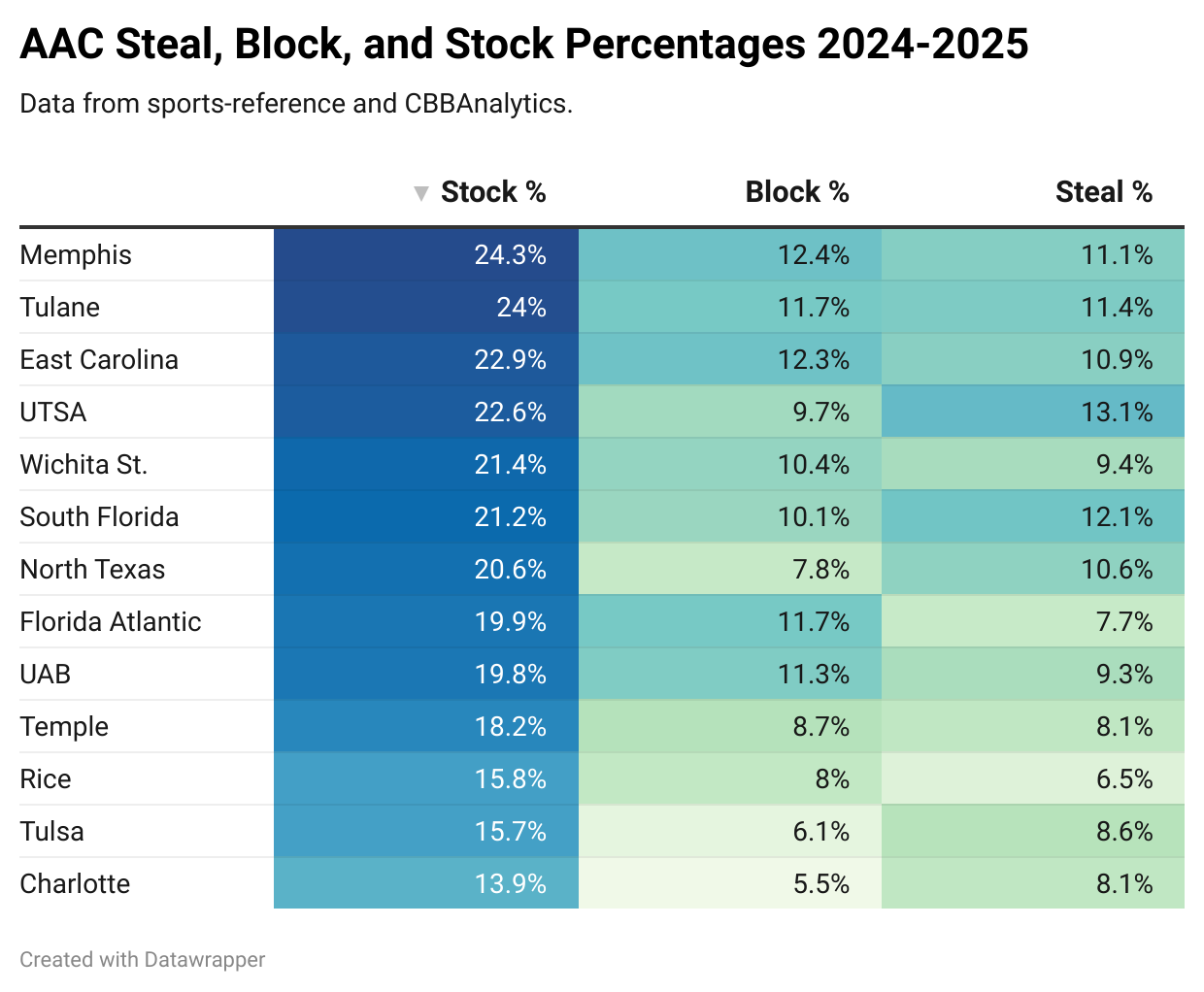

As a unit, the 49ers simply boasted no defensive playmakers, posting the conference’s lowest stock (steal + block) rate by almost two percentage points. Charlotte struggled to produce disruptive events without hacking its opponents: the Niners committed an average of 2.38 personal fouls for every steal or block they accumulated, one of the nation’s worst ratios.

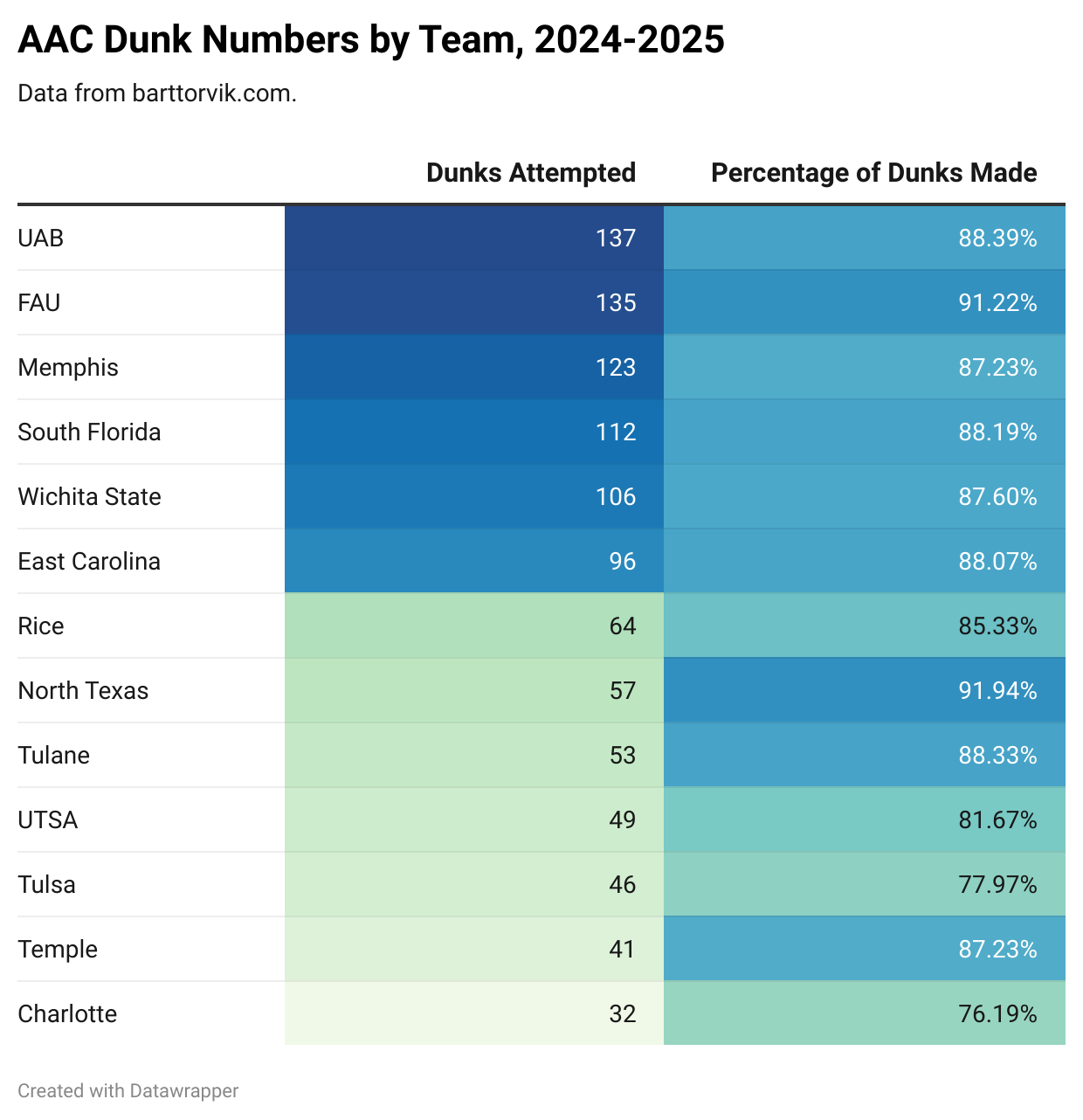

It’s worth pointing out that the roster’s general lack of athleticism almost certainly correlates to Charlotte’s low levels of playmaking on both offense and defense. Dunks are a primitive but typically effective proxy for estimating athleticism; the Niners finished last in the conference in both dunk attempts and FG% on dunk attempts.

Future outlook

Nowadays, it’s difficult to project program trajectory in mid-major college basketball because nearly all of us are playing the same game: import a flock of new players, lose the best ones to the transfer portal, repeat the cycle and hope everything gels. Charlotte, as the 2024-2025 campaign made painfully apparent, is no different. With many teams in the American carrying similarly pitiful NIL budgets, the factors that differentiate programs are tactical prowess and talent identification.

As we enter the third season of his tenure, where does Fearne rank among the pantheon of AAC coaches? Although he seems to be a solid in-game strategist, I will admit I’m skeptical. The 2023-2024 season was Charlotte’s most memorable since Lutz departed, but Fearne’s interim tag was removed solely off the strength of the magical midseason run: the 49ers started 6-7, ended on a 2-4 skid, were deemed one of the nation’s 75 luckiest teams by KenPom, and finished 120th in KP (14 spots worse than they did in Sanchez’s final year).

The only member of last season’s transfer haul (Blackmon, Thomas, Metskhvarishvili, Rosado, Szymczyk, and DePaul wing Jeremiah Oden, who missed the entire year with injury) to make an impact was Rosado. Oden, among the best of the group, would have provided a much-needed burst of athleticism and wing scoring, but it’s hard to imagine him having a significant effect on the season’s result.

From top to bottom, Charlotte was probably the least talented team in the American — although Lu’Cye Patterson’s last-minute departure admittedly put the coaching staff in a bind, it’s hard to ignore how ineffective the backcourt ended up being, and Szymczyk and the returners were particularly egregious busts up front. With everyone gone but Blackmon, Bradford, and Richart, Fearne must stage his first successful mass talent import or (likely) lose his job.